You Know Stereotypes Californians Are No One for Drugs and Health Food

Mental illness, substance corruption and concrete disabilities are much more than pervasive in Los Angeles County'due south homeless population than officials take previously reported, a Times analysis has found.

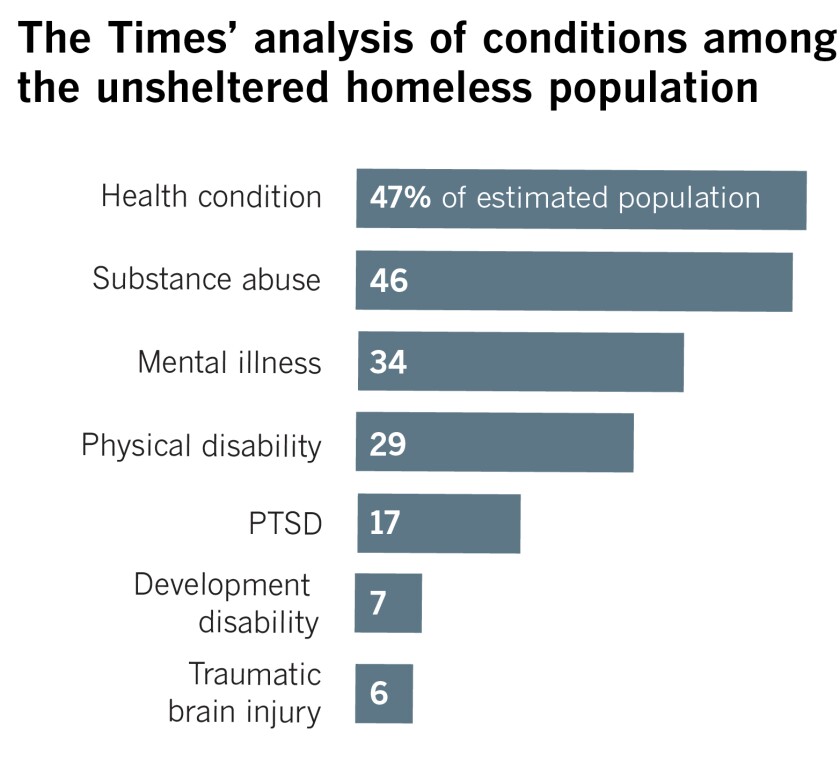

The Times examined more than 4,000 questionnaires taken as part of this year's indicate-in-time count and found that most 76% of individuals living outside on the streets reported beingness, or were observed to be, afflicted by mental illness, substance abuse, poor health or a physical disability.

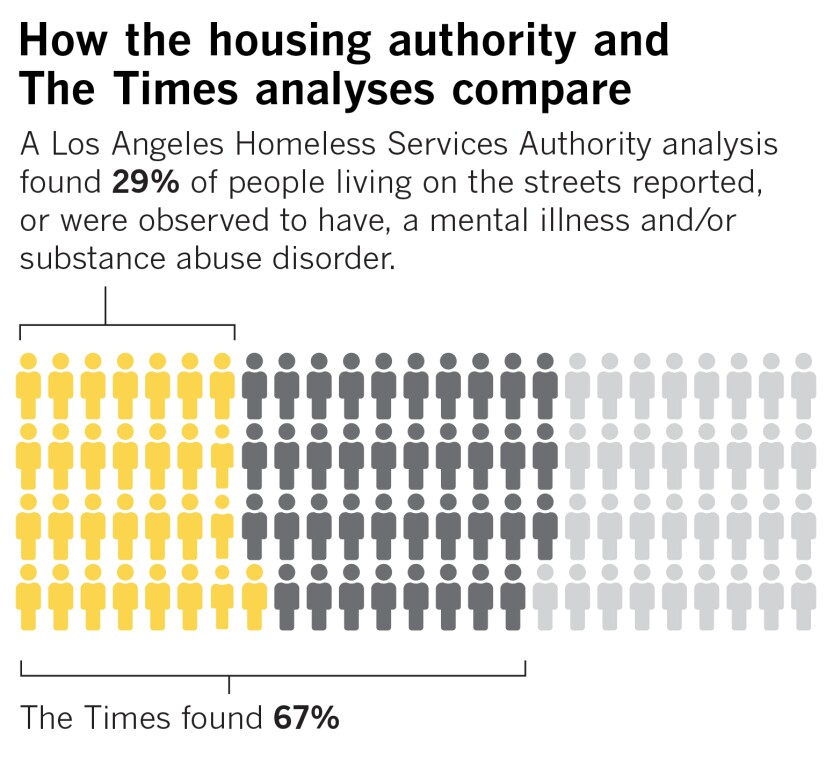

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, which conducts the annual count, narrowly interpreted the data to produce much lower numbers. In its presentation of the results to elected officials earlier this year, the agency said simply 29% of the homeless population had either a mental affliction or substance abuse disorder and, therefore, 71% "did not take a serious mental affliction and/or report substance use disorder."

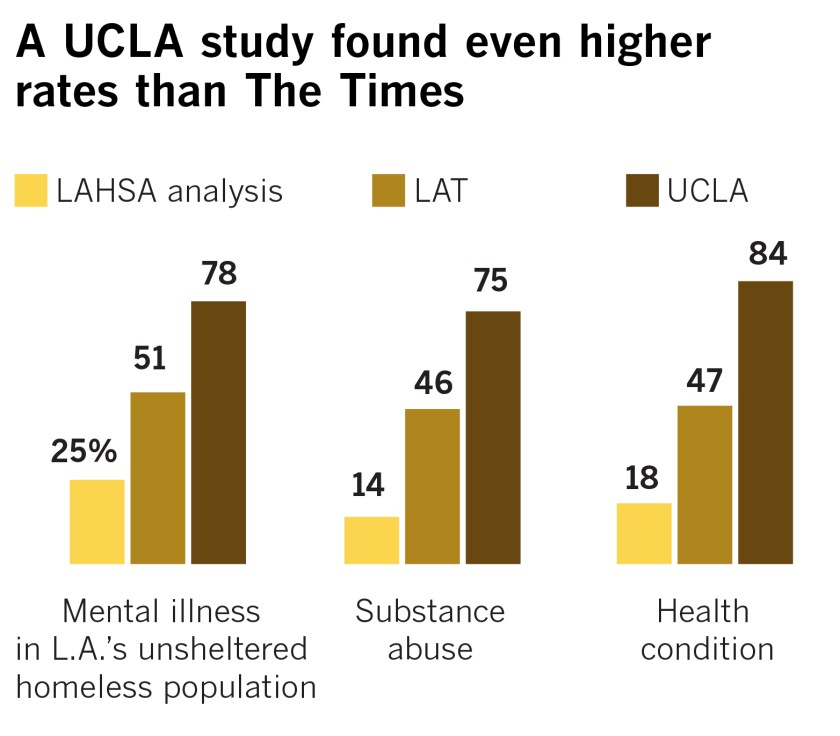

The Times, however, plant that about 67% had either a mental illness or a substance corruption disorder. Individually, substance abuse affects 46% of those living on the streets — more than three times the charge per unit previously reported — and mental illness, including mail service-traumatic stress disorder, affects 51% of those living on the streets, according to the analysis.

The homeless services potency did non dispute what The Times found. Rather, Heidi Marston, the agency'south interim executive director, explained that its report was in a format required by federal guidelines, leading to a different estimation of the statistics.

"Nosotros're acknowledging that at that place are more layers to the story," Marston said.

The Times analysis aligns with a national report released Sunday by the California Policy Lab at UCLA, which found even higher rates in most categories. It also found that a mental health "business" affected 78% of the unsheltered population and a substance corruption "business," 75%.

The findings lend statistical support to the public's frequent clan of mental illness, physical disabilities and substance corruption with homelessness. Simply neither the UCLA study nor the Times analysis suggests that these disabilities and health weather condition lone crusade people to end upwardly on the streets. Elected officials and researchers largely hold that California's affordable housing crunch and poverty are the master drivers of homelessness.

Rather, both the analysis and the study illuminate a population struggling with complex mental health conditions and concrete disabilities that interact and grow worse as people remain outside. Both data sets found mental and physical impairments to exist far more prevalent among those living on the streets than in shelters.

The Times constitute that 50% of unsheltered people had two disabilities at the same time and 26% had three all at once — a status known as tri-morbidity. UCLA researchers found tri-morbidity in half the population they studied.

The UCLA study also found that, among those who had been homeless for more than iii years, 92% had a physical health condition — anything from cancer to an abscess.

In Los Angeles County, 75% of homeless people are unsheltered and, in 2018, the statewide charge per unit of unsheltered homelessness was nearly the same.

Californians living in poverty and on the edge of homelessness have been crushed by soaring rents and heaven-high home prices in contempo years. A 2017 study by real estate house Zillow found that a 5% rent jump in Fifty.A. County would leave 2,000 more than residents homeless.

The research at UCLA, conducted by Janey Rountree, Nathan Hess and Austin Lyke, sought to offering empirical insight into a poorly understood community, Rountree said. The findings show a need for more attention to the physical and emotional distress of those on the street who are waiting for deficient housing opportunities.

She added that housing is crucial, but it won't lonely solve "these very deep medical, mental health and substance abuse issues."

"There really needs to exist an examination of the inflow of the unsheltered population, and are there issues of access to medical care, mental health care and to substance corruption handling that are just as important as thinking about how to business firm them immediately when they do go homeless," Rountree said.

Los Angeles County's homeless initiatives — along with almost initiatives across the state and the nation — emphasize what's known as a "housing showtime" strategy. The primary focus is on getting chronically homeless individuals off the streets and into permanent housing, where they can admission services to accost mental and physical issues.

But the number of chronically homeless people in Fifty.A. County — at nearly 17,000 every bit of January and growing — far exceeds the housing and shelters currently available. Even the thousands of new units beingness built with help from the $one.2-billion Proffer HHH homeless housing bond won't be enough to shut the gap.

"If beingness on the streets is bad for your wellness, so 'housing starting time' would be fine if everyone was going to be housed overnight," said UCLA associate professor Randall Kuhn, who wasn't involved in the research just said he plans to release a complementary study. "In the meantime, thousands volition go unsheltered for years and thousands will enter homelessness direct to the streets. What are we supposed to practise to help those people?"

At a time when cities and counties are struggling to respond to a growing number of street encampments, the UCLA study and Times assay enhance questions almost whether regime officials are taking the right arroyo and doing enough for people on the street who have little promise of getting into housing anytime soon.

The leaders of Gov. Gavin Newsom's new homelessness chore force have proposed enacting a legal right to shelter in California, which would force cities and counties to build enough shelter beds to suit whatever homeless person who seeks ane. The state program faces potential opposition, both from homeless advocates and from local officials, and lacks specifics on how the shelters would address the population'southward acute needs.

University of Pennsylvania professor Dennis Culhane, a longtime researcher on homelessness, said that a weak social safety cyberspace that in one case supported Americans with disabilities has been worsening for decades, which has left more people on the streets.

"Most people with mental illness take a toehold in the housing market that they hang on to for dear life. Only when it's shaken by this homo-made market disaster, they're the ones who lose out," Culhane said. "It's easier to focus on mental illness, and you think y'all're focusing on the problem when really it'southward something you tin can't see."

Advocates for homeless people tend to not focus their messaging on mental illness, disabilities or substance corruption out of business concern that doing and then unfairly stereotypes and stigmatizes those without a home.

Conference The Times on this yr's homeless point-in-time count prior to its release, Peter Lynn, executive director of the homeless authority, dedicated the agency's statistics on homeless people with disabilities and substance abuse bug. He attributed the idea that the numbers should be higher to perception bias.

Like other local and state officials, he has portrayed the homeless population as being much similar the wider population of housed Angelenos.

"What people remember are the cases that stood out, which are the cases of behavioral anomalies which is why, I think, people have a sense that there are more than people that have serious mental illness," Lynn said. "Most people with mental illness are housed. The vast majority of people with serious substance abuse issues are housed. They're using their substances in their bedrooms and in their living rooms and you're not watching information technology."

Speaking on behalf of Lynn, who is on medical leave, Marston said the agency reports demographic statistics in the same format as other cities effectually the state. They all follow guidelines gear up by the U.Due south. Department of Housing and Urban Evolution.

But she conceded that the reports leave out data that would give a more complete picture of what'southward happening on L.A. Canton's streets, including the role that trauma plays in mental illness and substance abuse.

"It's much deeper, and nosotros have an opportunity to dig into that," she said.

In a contempo email to members of the agency's board, Chairman Sarah Dusseault proposed that the agency work with the California Policy Lab to better understand the "urgent need of mental health or health services and to what extent do we demand to drastically increase access to those services for those individuals in gild to be able to house people." The data, she added, would aid the homeless services say-so "consider how to fund and implement shelter to home initiatives."

The Times found that the bureau'south analysis of its demographic survey reached the lower numbers by excluding several responses related to health and mental wellness issues, as well equally substance abuse.

For example, respondents' disclosures of having serious mental illness, depression or PTSD were counted only if they also answered a secondary question stating that information technology was "permanent or long term." That omission reduced the mental illness rate by 11.4 percentage points.

1 of the questions excluded past the bureau asked about the reasons participants became homeless. (Screenshots taken from Homeless Service Authority's survey)

These ii questions were used past the bureau to determine mental disease. (Screenshots taken from Homeless Service Authority's survey).

Patricia St. Clair, a senior member of the USC information team that analyzed the findings for the homeless authority, said the question was used to make the answers consistent with the federal definition of chronic homelessness. That definition requires a debilitating condition of a long duration, combined with a lengthy residence on the street.

She also said that omitting responses to the question was meant to screen out those who, for example, "had a bout of depression in boyish years."

Also, interviewers were asked to indicate if they observed a mental illness or substance abuse that was non disclosed by the respondent. Those observations were non included in the public report. If counted, they would have increased the charge per unit of mental affliction by 4.5 percentage points and substance corruption by nine percentage points.

St. Clair said responses to that question were not appropriate to use because the interviewers were non qualified to assess the symptoms of mental illness or substance abuse. Their observations were just for the purposes of weighting the responses, she said.

Questions most whether a person'south inability contributed to becoming homeless also were not counted, and would have added 3 percentage points to the mental illness and 4.v to substance abuse categories.

Differences betwixt the findings past The Times and those of UCLA could reflect potential biases in the information sources, Rountree said.

The UCLA study analyzed a national sample of near 65,000 questionnaires used to prioritize homeless people for housing. Considering disabling conditions are required to qualify, outreach workers have an incentive to find them.

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authorization'due south information, on the other paw, were nerveless as part of the local point-in-time count and were self-reported. As a result, respondents receive no benefit for providing sensitive data.

Source: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-10-07/homeless-population-mental-illness-disability

0 Response to "You Know Stereotypes Californians Are No One for Drugs and Health Food"

Post a Comment